Asia In News

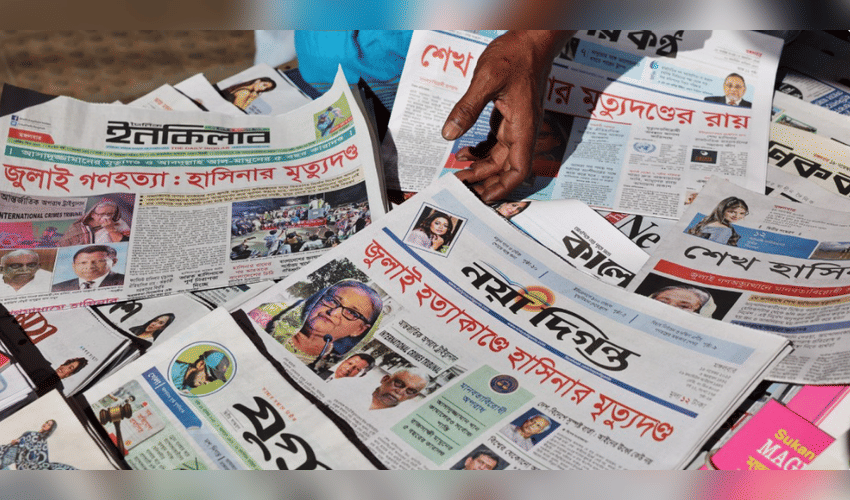

Bangladesh Gen-Z is struggling to secure political influence after removing Hasina from power.

Thousands of Bangladeshis initially gathered to hear the plans of the student activists who overthrew long-time leader Sheikh Hasina and later formed a new political party. But the momentum that helped them rise has not easily translated into electoral strength. The National Citizen Party (NCP), led by students who promised to break decades of nepotism and two-party dominance, is now struggling to convert its street power into votes as the February elections approach. Despite high expectations, the party is facing well-established rivals with deep networks and resources.

NCP chief Nahid Islam, a prominent figure in last year’s deadly anti-government protests and a former member of the caretaker administration under Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, admits the organisation is still weak because it had little time to develop. Even so, he says the group remains committed to the challenge. Opinion polls show the NCP in third place with just 6 percent support, well behind the BNP, which leads with 30 percent, and Jamaat-e-Islami with 26 percent.

Some early supporters say they are disappointed. Activist Prapti Taposhi, who helped lead the uprising, says the NCP’s actions do not match its claims of being centrist, and that the party hesitates to take timely positions on issues such as women’s and minority rights. The party’s inability to win any seats in the Dhaka University student elections-despite the campus being the centre of the movement that toppled Hasina-has added to the growing frustration.

The political environment remains tense. The Awami League, still banned from contesting elections, has warned of unrest if the restriction is not lifted, raising concerns for the nation’s garment industry. Meanwhile, the NCP’s organisational weaknesses, lack of funds, and unclear stance on key issues have pushed it to consider alliances with larger parties, including the BNP and Jamaat. Some within the party acknowledge that contesting independently may leave them without a single seat, although analysts warn that forming alliances could dilute the party’s revolutionary appeal and make it look like just another political faction.

Most of the students who united briefly to oust Hasina have returned to their old political groups, leaving only a small fraction to build the NCP from scratch. The party now faces rivals with long-established networks that reach deep into rural communities. Fundraising is also a struggle, with members relying on salaries, small donations, and crowdfunding. Some aspirants, like 28-year-old Hasnat Abdullah, campaign door-to-door, telling villagers that leadership should be about fair use of public funds, not handing out money for votes. Allegations of corruption—denied by the party—have further damaged its image.

Still, many young Bangladeshis see the NCP as an opportunity for a more egalitarian political culture, free from dynastic influence and driven by ordinary citizens. In November, the party launched an unusual nationwide search for candidates, interviewing more than a thousand applicants from all walks of life, including a rickshaw puller who took a day off work and a student partially blinded by police pellets. Their vision has also attracted professionals like Tasnim Jara, a doctor who left a thriving career in Cambridge to help build the NCP.

Senior leaders from the BNP and Jamaat say engaging with youth is essential, as young people will shape the future of Bangladeshi politics. For its part, the NCP says it is thinking beyond the immediate election, aiming for long-term structural reform. Whether they win seats or not, leaders say their participation itself represents a new direction for the country.